Written by Guillaume Van de Wege – You can access Guillaume’s full range of articles on Substack here.

The premise of this article is to open a panel through which Manchester United‘s fitness woes can be contextualised. Since there is no access to training or data on physical parameters, this blog does not attempt to definitively clarify the core instigator(s) of this evident disarray.

Nonetheless, the aim is to shed light on how these problems emerge through articulating basic training principles in an understandable and responsible manner.

Introduction

Throughout this article, several training concepts will be explored in an apprehensible manner and then linked in any capacity to Manchester United’s 2023-2024 season.

For sports scientists and/or physical coaches who plan the demands of a training session (this is not the responsibility of the head coach), the split between the profile of the sport (which demands does this sport put on its athletes) and the profile of the athlete (what does an athlete who deals with those demands look like) is essential.

Football, for example, is an intermittent (start-stop) sport; largely consisting of jogging and walking, divided by high-intensity sprints, leaps, duels under contact, shooting the ball, …

The footballer must, therefore, be able to (1) endure low-intensity actions like jogging and walking, (2) perform to their maximal potential in high-intensity actions, and (3) quickly recover between high-intensity actions and (4) maintain quality across all actions.

Every person, every athlete, and every footballer has a physical status (your current fitness) and a potential to reach. Training is how that potential is achieved – and it is the responsibility of the staff to ensure those players get as close to their potential as possible. This is one of the less than a handful of core responsibilities of a coaching staff.

Football is a complex sport on a physical level due to multiple energy-delivered systems (for low-intensity endurance and high-intensity strength/power/speed at random times) that need to be fit. Therefore, the preparation phase is crucial to building up the low-intensity system (through volume), which is needed to improve the subsequent high-intensity systems (through intensity).

The (head) coach(es)—Erik ten Hag, Rene Haké, and Ruud Van Nistelrooy plan session exercises based on correction (what can we do better) or curriculum (a pre-made plan of what we train). Charlie Owen, among other physical coaches, adjusts exercise rules, players, durations, and distances to train strength, speed, power, coordination, and endurance. Volume and intensity are also domains largely overseen by the physical staff.

Volume and Intensity

Volume refers to the length or duration of exercise, either in the short-term (one session of two hours), the medium-term timespan (four weeks), or the long-term (one season).

On the other hand, there is intensity, which is… yes, the intensity of a session. Space or player count are useful didactics to play with to influence intensity – the shorter the space and the fewer players, the more intense an exercise becomes. View the 10v10 on 90×45 metres as one end of the less intense exercise, while 2v1 on 10×5 metres is very intense.

Together, volume and intensity are often bunched together as the load is put onto players.

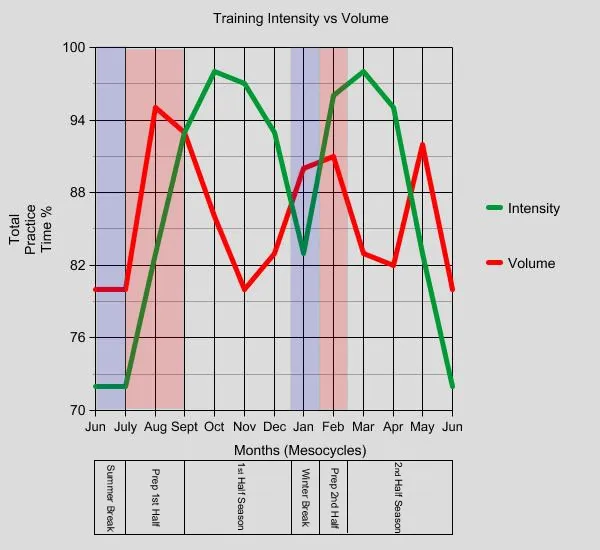

It must be understood that throughout a season, volume and intensity interchange based on the demands of athletes and their sport (in function of the timing of their games). Gymnastics, for example, has a very short competitive phase, while team sports such as football have two (if there is a winter break) long semesters of competition phases. Therefore, a pre-season, or preparation phase, is essential to prepare the fitness for the season ahead – where it is only maintained and not improved.

In those preparation phases – which should be at least 6 weeks long – volume has the upper hand over intensity. Intensity is progressively ramped up throughout this pre-season. Remember, volume means longer or more sessions – a common practice that is often seen on pre-season tours is Premier League teams having double sessions.

As intensity ramps up throughout the preparation phase, volume starts to decrease in anticipation of the first competitive games. Around the start of the competition phase, a complete cross-over occurs, where intensity is the primary factor between the two. Until the winter break (or end of the season, for some leagues), teams now enter a phase where they maintain the fitness built up throughout the preparation phase.

That crossover point is, however, not insignificant.

It was during that crossover window in August and September of 2023 that Manchester United sustained their first significant muscular injuries. A pre-season schedule with short training volume (days between games) or bad practice in general will also start the season unfit. A common response is to adapt the intensity or volume, resulting in muscular injuries.

In order to finish the season strongly (from February-March to May), the length of the aforementioned preparation phase is crucial. This phase elevates the level at which fitness can be maintained and “recycled” throughout the competition phase and, therefore, needs to stretch over multiple weeks to be significant. The “golden standard” of pre-seasons goes from six to eight weeks, albeit not often possible at this level (with internationals going on holidays).

Manchester United’s international players reported to training at Carrington on the 5th of July, 2023 – with their first competitive game (home against Wolverhampton Wanderers) on the 14th of August. That totals to five and a half weeks of preparation, with too much of that time spent on intercontinental flights and coast-to-coast flights in the United States, which made sense from a commercial viewpoint; and less so from a sporting perspective. That travel disrupts training in the most crucial phase. This is a fault of Manchester United’s sector, which is obliged to visit other continents.

In the 2024-2025 pre-season, players and staff reported to testing and training on July 8th, which gives the non-internationals five and a half weeks to prepare for the Premier League opener. The Community Shield final is played four days beforehand.

Tapering

The next training concept relevant to this framework is the idea of tapering.

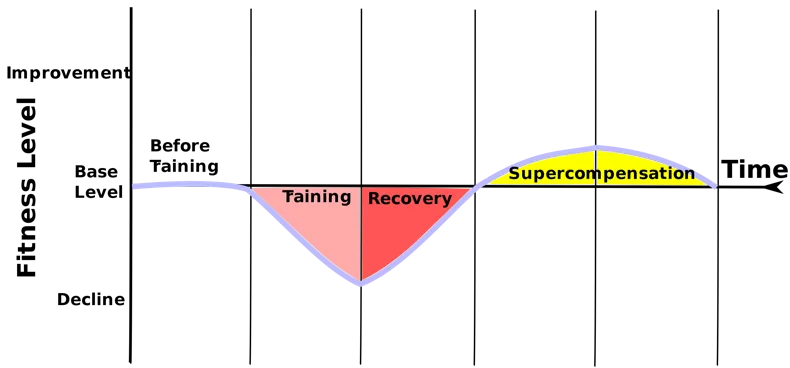

Tapering is where load (volume x intensity) is decreased to improve performance. The idea is to reduce stress and create super-compensation during a time period before a competition—for example, the competition phase on a large scale (season-long = macrocycle).

The caveat to tapering is not to decrease intensity but only volume—for example, reducing the amount or length of training sessions. While a decrease in intensity could also relieve stress, it would also induce a detraining effect.

However, the concept of tapering is not only applied in the macrocycle, but also on lower scales – in the microcycle (one week, before a game), and in the mesocycle (4-6 weeks).

Unplanned tapering within a mesocycle is a common mistake, because it is a knee-jerk reaction to injury problems within troubled teams – in youth teams, but also at the absolute highest level.

It is a reaction to “there are too many injuries; we need to reduce intensity to prevent more.” The physiological mechanism behind that is that games become the most intense demand on un(/mis)trained players, who then sustain more injuries, as their bodies are unfit to deal with those demands.

It must also be mentioned that Erik ten Hag admitted to “never having so many injuries in over ten years of management”, which brings unfamiliar complications. Each player needs their own individual schedule to return to different intensities (individual/grass/team training), which hinders the original training planning laid out at the start of the season. The more injuries, the bigger the cascade of injuries throughout a season.

Strategy

Another (more global) consideration is the strategy by which Manchester United approach games.

Just like the way the profile of a sport influences its athlete, the strategy influences the profile of a footballer. Erik ten Hag famously intends Manchester United to become the best transitional team in the world (which doesn’t mean leaving huge gaps in midfield).

Those gaps appear, however, due to multipe strategic factors that do not need to be expanded upon in this blog. Larger spaces and more high-intensity runs *roughly* equate to a heftier tax on endurance and speed.

Long balls and the duels on either the ground or in the air, under the stress of contact, tax the strength, power, and muscular endurance.

The intensity or volume on matchday doesn’t directly contribute to injuries unless players are not trained in a responsible manner – think of the larger scale; the period needed to push athletes to a fit status, or the shorter scale, the warm-up itself.

This scale is a theoretical model through which the phenomenon of injuries are understood; Tax refers to “what the players execute”, while taxability is “what the players can endure”.

Muscular or tissue-related injuries occur when taxability outweighs tax. In order to secure the quality of an athlete or team’s taxability, a few measures can be taken across different dimensions.

In order to increase the taxability:

- SQUAD BUILDING: Recruit players with high-end (relevant) physical traits at relevant positions. This is partly personal preference, partly what has worked for the great Premier League teams from 00 to Manchester City in 2024.

- SPEED in attack

- STRENGTH and POWER across the board

- TALL HEADERS across the backline + one or two in front

- TRAINING: Coaches are “trainers” and are responsible to train the players in the most responsible way. Train the players to obtain and maintain their physical potential throughout the competitive season.

In order to decrease the tax:

- MANAGEMENT: Manage the load of the players in the most responsible way through distributing minutes across the player pool.

- GAME PLAN: Manage the demand of the players within the game plan; how many “passengers” are there in the team? Why is one midfielder compensating for the lack of workrate by the frontline?

These are the tangible items that improve “physicality” in a team.

The game inherently will still always be a players’ game, and the aim for the coaching staff is to set up the right players in the right roles and train/lead them in the most physically and mentally responsible way.

This is what Manchester United failed to do in 2023-2024, considering the muscular non-contact injuries which are a result of overload (tax>taxability). Attempting to improve the physicality through overload is no valid reason, nor an excuse to endanger the health of the players – irrespective of short- or long-term goals.

Plenty of media (some made sense, some did not) covered the injury crisis with either basic training principles, which are meaningless and never taunted with by professional teams; while other reports were more to the continuum of hit-and-hope-and-probably-miss. There was always lots of talk surrounding intensity, but never of volume.

Managers or head coaches happily blame the schedule as the main instigator for injury problems. Squads in England are however big enough to distribute minutes in order to manage the workload of players. This is what Erik ten Hag’s team has not done in the 2022-2023 season, which overreached players and partially started the crisis of 2023-2024. It remains to be seen what influence INEOS will exert on this topic, if any at all.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How much of the crisis was down to (bad) luck?

A: Muscular injuries that occur without external contact are down to an overload, meaning the tax was heavier than the taxability. The question is whether the tax (training load, playing style, minute distribution) was too high, the taxability (training status) too low, or both. This question has no clear answer due to the lack of information, but is what we explore in the blog above.

Q: How much of it is down to Erik ten Hag?

A: This is unclear as there is not enough information to declare it either a tax or taxability issue (or both), but the manager is indirectly responsible. This is why information about Shaw’s ability to play 60 games in a season is shared by the head coach, or why the head coach is calling the injuries bad luck.

Q: How likely is it to occur during the 2024-2025 season?

A: For one, Manchester United already prepared themselves in a more responsible manner this pre-season logistically and in terms of duration. This league is uncharted territory for Erik ten Hag in terms of intensity in mid-week and weekend games, however. Time will tell whether he will change his approach.

Q: Are the injuries a case of short-term pain for long-term gain, to improve physicality?

A: No. Overloading players is not a goal or a tool to reach a higher level of physical status. It is not a means to improve physicality. That is irresponsible advice that needs to be called out. To securely train every individual is never failsafe – injuries will unfortunately happen. But the rule of thumb is that players do not need injuries in order to reach their physical potential.

Q: How can the coaches improve the players’ fitness during the season?

A: Ideally, this happens in a 6-week pre-season. Given United’s commercial obligations, that has not happened in the years under Erik ten Hag. In the season, the mid-week training (furthest from the previous and next game) is the heaviest training in terms of physical load. For teams in Europe, with mid-week games, that becomes unpractical. Training is then largely focused on recovering, by which that physical potential will not be hit if not hit during pre-season.

Q: Who is to blame?

A: There is of course not one actor or factor to blame. The coaching staff can be held accountable for not adapting the game plan to the physical level of the team which was unfit, insisting on the incoherent instructions out of possession.

Perhaps a few individual players, the medical staff and coaches can be held accountable for rushing players back from injury, evidently suffering from recurring injuries shortly after. Key examples are Luke Shaw and Mason Mount. It is unclear to which extent powers were at play here, all we can be sure of is that the process was not handled correctly.

Finally, the planning of United’s pre-season tours has hindered the development of the training. The players had more than three days between pre-season games twice. Three days allow for one day of training that is not focused on recovery or activation for the next game. Keep in mind the travel hours from coast to coast within those three days or less.

Reminder: You can access Guillaume’s full range of articles on Substack here.